Agitation in Alzheimer's Dementia (AAD)

Why Early Detection Is Vital

Agitation Is a Common Manifestation in Patients With Alzheimer's Dementia1

Estimated number of U.S. adults aged ≥65 years living with Alzheimer’s dementia:

It is estimated the number will almost double by 2060.

The manifestations of Alzheimer’s dementia include a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including agitation1-4

individuals with Alzheimer’s dementia1

Approximately 45% of community-dwelling patients and 53% of nursing home residents exhibit agitated behaviors during the course of Alzheimer’s dementia.1,2,5

Agitation in Alzheimer’s Dementia Displays a Broad Spectrum of Symptoms6,7

Agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia is a common and treatable condition with a broad range of symptoms. It requires management strategies distinct from those used for cognitive impairment.6-8

Agitation Can Manifest as Both Non-Aggressive and Aggressive Behaviors

Non-aggressive behaviors such as wandering, pacing, and repetitive questions may not be immediately recognized as part of agitation and are often dismissed as acting out.

Agitation in patients with a cognitive impairment or dementia syndrome is defined by the IPA as excessive motor activity, verbal aggression, or physical aggression. Examples of each include the following behaviors7,9:

Agitation Is Prevalent Across Care Settings and Alzheimer’s Dementia Severities1

Care Setting1,5

Alzheimer’s Dementia Severityb,c,1

Although agitation occurs more frequently in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's dementia, it can occur in patients with milder dementia as well.1

aNursing home percentage reported includes those with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia.

bOf the 320,886 eligible patients, 78,827 (24.6%) could be assigned to explicit AD/dementia severity categories over a 2-year period.

cAdapted from a retrospective database study of 320,886 community-dwelling patients with ≥1 electronic health record (EHR) indicating Alzheimer’s disease/dementia. Agitation was identified using diagnosis codes for dementia with behavioral disturbance and EHR abstracted notes records indicating agitation symptoms compiled from the International Psychogeriatric Association provisional consensus definition. Patients who had records containing valid quantitative MMSE scores or explicit terms for only one level of AD/dementia severity were categorized accordingly as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe".

Agitation Is One of the Most Costly Aspects of Alzheimer's Dementia Care and Increased Healthcare Resource Utilization3,4,10

The presence of agitation may increase the likelihood of patients with Alzheimer's dementia being placed in long-term care (LTC) facilities.5

Agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia is associated with an increased economic burden for both individuals and healthcare systems10,11

In a real-world study of 1,349 patients with early cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s dementia, patients identified as having agitation demonstrated significantly higher healthcare resource utilization and costs than patients without agitation.12

Agitation in Alzheimer’s Dementia Is Associated With Significant Negative Patient Outcomes and High Caregiver Burden1,11

Overall, agitation versus no agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia has been associated with1,5,12-16:

Accelerated disease progression

Functional decline

Decreased quality of life

Greater comorbidities

Increased use of concomitant therapies

Increased risk of hospitalization/

Earlier death

In long-term care, agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia has been associated with these additional consequences5:

Falls

Fractures

Infections

Higher medication use

Other neuropsychiatric symptoms

Agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia has been associated with significant caregiver burden that increases with severity. It is a factor for burnout, reduced workability, and overall poorer health among caregivers. These negative outcomes are common to both professional and family caregivers.10,11,32-35

General health decline

Reduced quality of life

Depression

Anxiety

Embarrassment & guilt

Social isolation

Increased use of clinical services

Overview of the Pathophysiology of Agitation in Alzheimer’s Dementia

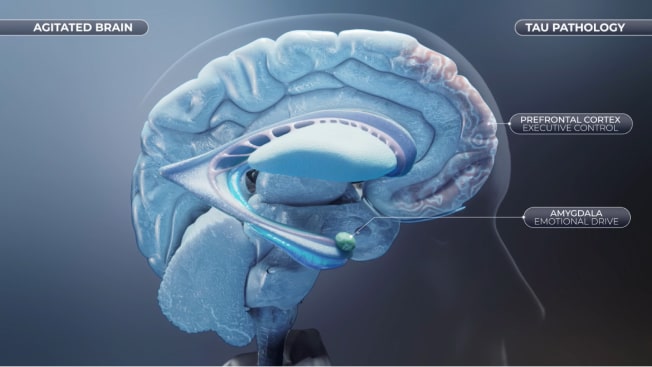

Agitation in Alzheimer's Dementia: Tau Pathology and Neurodegeneration

The presence of accumulation of aggregated Tau protein (also called neurofibrillary tangles) and aggregated amyloid beta peptides (also known as senile plaques), two of the main hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease, can be found in high density in the prefrontal cortex and subcortical regions. The consequent neurodegeneration leads to functional impairment and disruption of the balance between executive and emotional drive and might be directly associated with the risk of developing agitation in Alzheimer's dementia.17-20

- Agitation is associated with Prefrontal Cortex tau pathology and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer's dementia21,22

- The amygdala is severely impacted in Alzheimer's dementia, with tau pathology observed at relatively early stages of the disease23,24

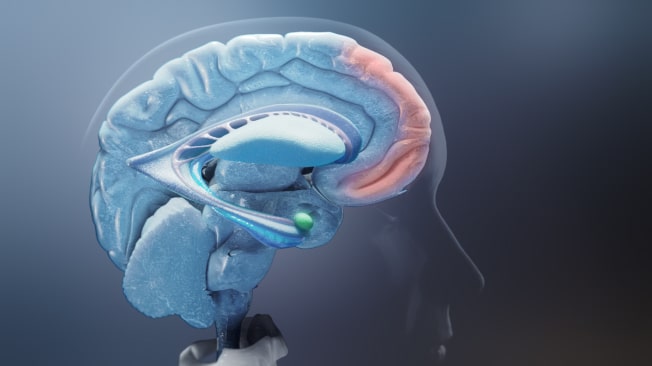

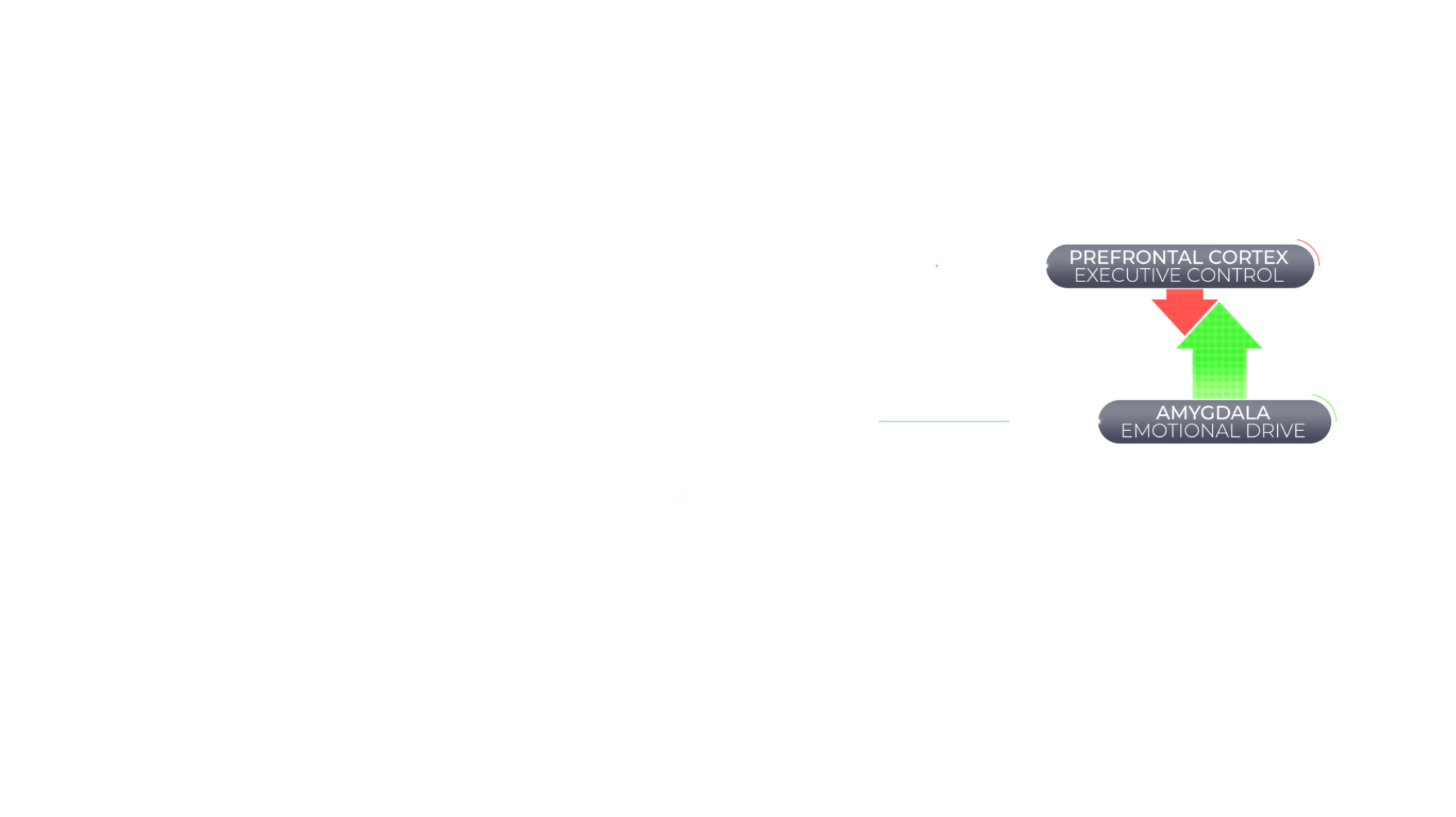

Agitation in Alzheimer's Dementia Is Associated With an Imbalance Between Executive Control and Emotional Drive

When the brain is functioning normally, behavior is regulated by a balance between a top-down executive function of the brain (controlled by the prefrontal cortex) and bottom-up emotional drive (controlled by subcortical regions, including the amygdala). However, the brain can suffer structural and chemical changes associated with Alzheimer's dementia that might disrupt this balance and have behavioral consequences.36,37

Agitation in Alzheimer's dementia is associated with an imbalance of brain activity between the prefrontal cortex, a key contributor of executive control, and the amygdala, a key mediator of emotional drive.36,37

Dysfunction of Norepinephrine, Serotonin, Dopamine (NSD) Neurotransmitter Systems May Contribute to Imbalance Between Executive Control and Emotional Overdrive

An underlying cause of agitation in Alzheimer's dementia may be dysfunction in the NSD neurotransmitter systems, which may result in an imbalance between top-down executive function and bottom-up emotional drive. Alterations in these systems leading to agitated behaviors include norepinephrine hyperactivity, serotonin deficits, and dopamine dysregulation.25,38

Current Approaches and Unmet Needs in Recognition of Agitation in Alzheimer’s Dementia

Agitation behaviors are underrecognized, despite being among the earliest and most common manifestations in Alzheimer’s dementia25

Currently, HCPs rely on caregiver reports to identify agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia, given symptom identification most often occurs at home. However, caregivers do not understand the full breadth of agitation symptoms. As a result, some symptoms may not be reported to the HCP.26

Effective identification and management of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia depends on clear communication among HCP-caregiver. Claim-based studies reveal that agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia is often underdiagnosed, with only a small percentage of symptomatic patients receiving a diagnosis.1,27

This gap may stem from differing understandings of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia among caregivers and HCPs due to the diverse presentation of

symptoms.2,26

Poor communication between caregivers and HCPs may negatively impact patient care.27

The IPA set a new standard for the definition of agitation in cognitive disorders, provided recommendations for the implementation of the criteria in research and clinical care, and offered a solid foundation for the recognition of agitation.7

The IPA definition of agitation in cognitive disorders includes four criteria7:

The patient meets the criteria for cognitive impairment or dementia syndrome

The patient exhibits ≥1 agitation behavior(s) with emotional duress that is persistent or frequently recurrent for ≥2 weeks or the behavior represents a dramatic change from the patient’s usual behavior*

The behaviors are severe and associated with excess distress or produce disability beyond that due to cognitive impairment

The behaviors cannot be attributed to another psychiatric disorder or medical condition, including delirium, suboptimal care conditions, or the physiological effects of a substance

*In special circumstances the ability to document the behaviors over two weeks may not be possible and other terms of persistence and severity may be needed to capture the syndrome beyond a single episode.

The Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) is a clinically validated scale commonly utilized in clinical trials. It measures the frequency of 29 specific behaviors associated with agitation.6

- Hitting (including self)

- Kicking

- Scratching

- Grabbing people or things inappropriately

- Pushing

- Hurting self or others

- Throwing things

- Cursing or verbal aggression

- Spitting

- Tearing things/destroying property

- Screaming

- Biting

- Pacing, aimless wandering

- Trying to get to a different place

- Inappropriate dressing or disrobing

- Handling things inappropriately

- General restlessness

- Performing repetitious mannerisms

- Complaining

- Constant unwarranted requests for attention/help

- Repetitive sentences or questions

- Negativism

- Hiding things

- Hoarding things

- Making physical sexual advances or exposing genitals

- Eating or drinking inappropriate substances

- Making strange noises

- Intentional falling

- Making verbal sexual advances

*Other behaviors have low rates of occurrence.

The CMAI Scale6

29 Agitated Behaviors:

The CMAI measures the frequency of 29 agitated behaviors within the previous 2 weeks, rated on a 7-point scale.

Administering:

The CMAI can be self-administered by caregivers or completed by healthcare practitioners.

Total Score:

Sum of individual behavior scores. Higher score indicates more frequent agitation.

ICD secondary diagnosis codes allow providers to capture additional information on dementia conditions, including presence of agitation.

Primary Diagnosis Code25

If required, code Alzheimer’s Disease using one of the following diagnosis codes:

G30.0

Alzheimer’s disease with early onset

G30.1

Alzheimer’s disease with late onset

G30.8

Other Alzheimer’s disease

G30.9

Alzheimer’s disease, unspecified

Secondary Diagnosis Code40

Code Agitation Associated with Dementia using one of the following diagnosis codes:

F02.811

Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere, unspecified severity, with agitation

F02.A11

Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere, mild, with agitation

F02.B11

Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere, moderate, with agitation

F02.C11

Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere, severe, with agitation

AASC®: Filling the Gap With a Caregiver Screener Tool9

Engaging in proactive conversations with caregivers may enhance the monitoring and reporting of agitation symptoms.

The AASC® is a brief, pragmatic caregiver screener tool developed based on the IPA criteria to foster caregiver awareness to facilitate caregiver-HCP communication and early recognition of agitation symptoms.

Current Treatment Paradigm

Interested in learning about the AASC® development?

Reference(s)

1. Halpern R, et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(3):420-431. 2. Alzheimer’s Association. 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement 2024;20(5). 3. Anatchkova M, et al. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(9):1305-1318. 4. Antonsdottir IM, et al. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(11):1649-1656. 5. Fillit H, et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(12):1959-1969. 6. Cohen-Mansfield J. Instruction Manual for the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI). 1991. Rockville, MD: Research Institute of the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington. 7. Sano M, et al. Int Psychogeriatr. 2023;1-13. 8. Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, et al. Gerontologist. 2020;60(5):896-904. 9. Clevenger C, et al. One Minute to Recognition: The Agitation in Alzheimer’s Screener for Caregivers (AASC®). The Gerontological Society of America Annual Scientific Meeting; November 8-12, 2023; Tampa, FL. 10. Kales HC, et al. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. 11. Schein J, et al. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;88(2):663-677. 12. Jones E, et al. J AlzheimersDis. 2021;83(1):89-101. 13. Koenig AM, et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(1):3. 14. Peters ME, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(5):460-465. 15. Scarmeas N, et al. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1755-1761. 16. Banerjee S, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):146-148. 17. Hu X, Meiberth D, et al. Anatomical correlates of the neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12:266-77. 18. Guadagna S, Esiri M, et al. Tau phosphorylation in human brain: relationship to behavioral disturbance in dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2798-806. 19. Tekin S, Mega M, et al. Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:355-61. 20. Trzepacz P, Yu P, et al. Frontolimbic atrophy is associated with agitation and aggression in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:S95-S104.e1. 21. Tissot C, et al. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2021;7(1):e12154. 22. Banno K, Nakaaki S, et al. Neural basis of three dimensions of agitated behaviors in patients with Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:339-48. 23. Wright C, Dickerson B, et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of amygdala responses to human faces in aging and mild Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1388-95. 24. Gonzalez-Rodriguez M, et al. Brain Pathol. 2023;33(5):e13180. 25. Lanctot KL, et al. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2017;3(3):440-449. 26. Stella F, et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(12):1230-1237. 27. Richler LG, et al. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2023;31(1):22-27. 28. Clevenger C, et al. Study protocol: quantitative evaluation of The Agitation in Alzheimer’s Screener for Caregivers (AASC), a novel tool for improving recognition of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC): July 28-August 1, 2024: Philadelphia, PA. 29. Carrini C, et al. Front Neurol. 2021;12:644317. 30. Nordstrom K, et al. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):3-10. 31. Reus IV, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):543-546. 32. Palm R, et al. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1463-1470. 33. Isik AT, et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(9):1326-1334; 34. Brodaty H and Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1990;24(3):351-361; 35. Patrick KS, et al. Psychogeriatrics. 2022;22(5):688-698 36. Rosenberg PB, Nowrangi MA, Lyketsos CG. Mol Aspects Med. 2015;43-44:25-37. 37. Ochsner KN, et al. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(11):1322-1331. 38. Gannon M, Wang Q. Complex noradrenergic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: Low norepinephrine input is not always to blame. Brain Res. 2019;1702:12-16. 39. Rabinowitz J, et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(11):991-998. 40. ICD10Data.com. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://www.icd10data.com/.